In March, Consumer Reports released their independent findings of contaminants (or lack thereof) in 41 formulas. While the FDA now strictly regulates nutritional content and bacterial contamination, they do not scrutinize or standardize contaminants such as lead or arsenic.

One of the formulas on their “Good Choices” list (formula categories were “Top Choices,” “Good Choices,” and “Worse Choices”) was the formula I use for my own son, Kendamil Organic. It’s a whole cow milk based formula with organic ingredients, but it made the “Good” list instead of “Top Choices” because of elevated lead levels. For the other Kenda-Parents out there, CR only published findings for Organic and Classic (both cow’s milk based), but not for the popular Kendamil Goat.

Methodology

You can read the full methodology here.

CR examined standard contaminants and potassium levels. For contaminants, there are no U.S. federal regulations. It’s important to note though that the EU has formula-specific regulations and California has published important health limits. CR makes the following comments about potassium: “The tests also included an analysis of each formula’s potassium content. This was a check on the formula’s nutrition content, not its potential contamination. In 2024 the FDA put out warnings for certain formulas because they had excessive levels of potassium, which can be dangerous. The good news here is that none of the potassium levels measured in CR’s tests were over the maximum limit set by the FDA. Some of the formulas tested below the lower limit, but they weren’t so low as to be of concern.”

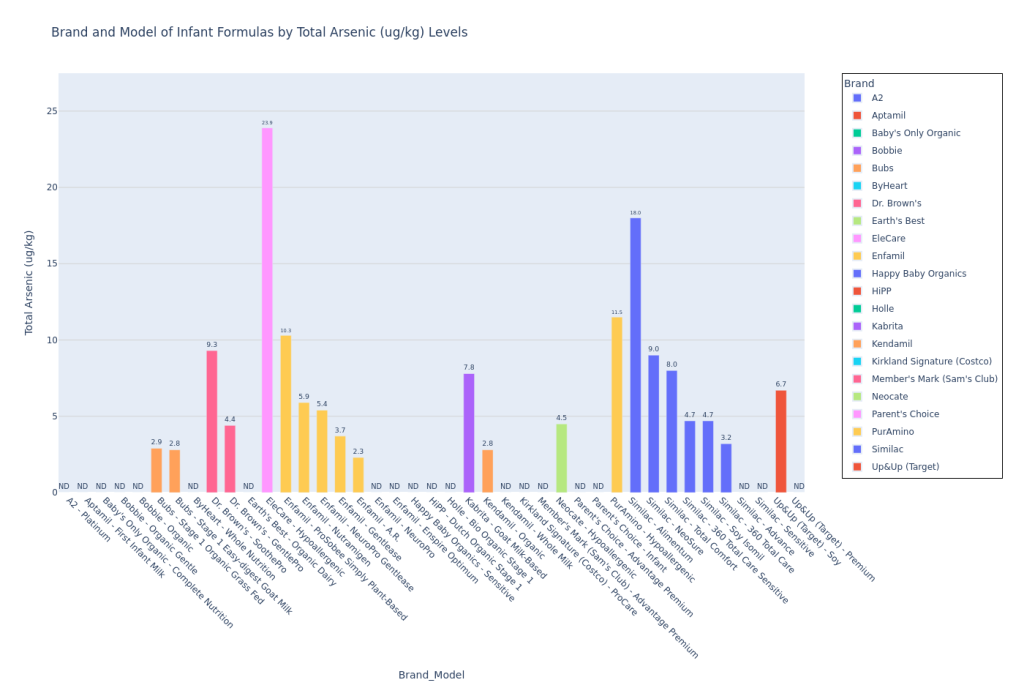

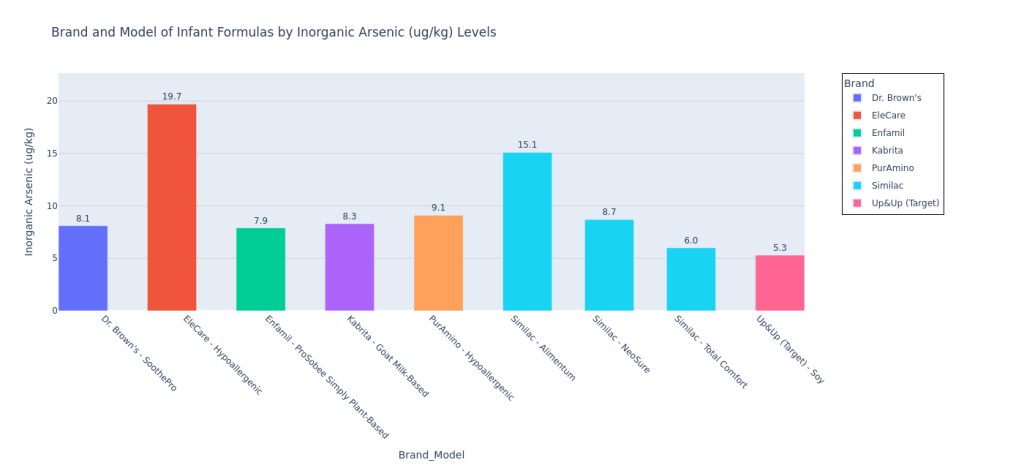

For arsenic, CR wrote in the footnotes for the data pdf that “Based on the risk assessment, only those formulas that had total average arsenic levels of 6.7 ppb and above were analyzed for inorganic arsenic. Levels below this would not likely pose a risk based on inorganic arsenic levels. At least one sample was analyzed for inorganic arsenic for each of these formulas.” I think this statement is a little confusing, since it says that only formulas over a certain total arsenic limit were analyzed for the inorganic variant, but then it goes on to say that at least one sample was analyzed for inorganic arsenic. Based on the raw data, it is evident that CR only measured inorganic arsenic for those formulas that exceeded the 6.7 ppb threshold for total arsenic. For those parents who use Enfamil Nutramigen, please note that CR did release a correction. They wrote that “This article, published March 18, 2025, has been updated to reflect that Enfamil’s Nutramigen formula did not have concerning levels of inorganic arsenic.”

One of the most important quotes from CR’s methodology document gives the following information about sampling: “Forty-one models of powdered baby formula were tested. Two or three samples, representing one to three lots, plus two duplicates were tested for potassium and all the contaminants, other than PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), at an accredited laboratory. PFAS analysis was performed on only one sample per model at another accredited laboratory.”

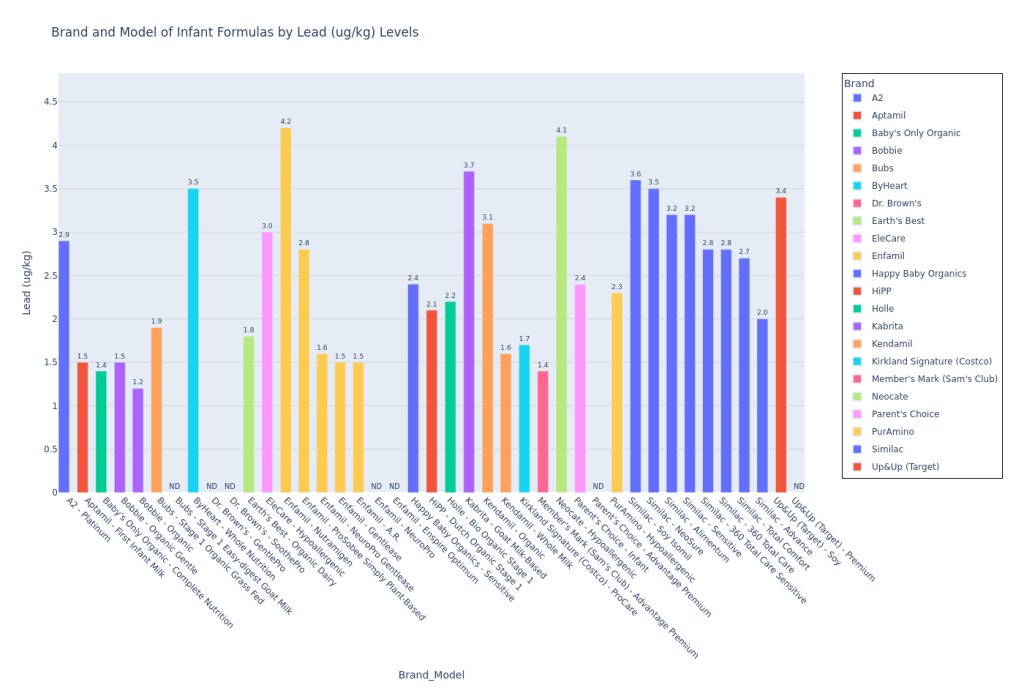

I do wish that CR had specified in their test results pdf (here) how many samples were taken from each model. Instead, we are told vaguely that “[t]wo or three samples, representing one to three lots, plus two duplicates were tested for potassium and all the contaminants, other than PFAS” were collected. This matters particularly for my situation. My son is on Kendamil Organic and Kenda-parents online are currently aflame about the elevated levels of lead (it’s a recurring topic on Kendamil Facebook pages that I follow). However, if lead can be in the environment, then it is possible that CR sampled from a lot with cows on a particular farm with higher levels of lead in the soil. At a minimum, CR tells us that they took 2 samples representing at least 1 lot. However, at a maximum, CR may have taken 3 samples representing 3 lots. If CR had told us that they had sampled 3 lots worth of Kendamil Organic, I would take their average lead measurement more seriously than if they had only sampled from 1 lot. Since they don’t tell us, we simply don’t know. A conservative (high anxiety?) mom like me will just assume the worst. For the purposes of this article, I will *assume* that CR contaminant values are accurately representative and can be extrapolated across all lots for a given formula model. I do recognize though that this is not necessarily good science, but I am doing my best with limited information and resources.

While in the test results CR reported contaminants in units that don’t care about amounts (ug/kg, which is equivalent to parts-per-billion, or ppb), their methodology document includes limits set by California health authorities which do rely on amount consumed per day. These limits are called Maximum Allowable Dose Level, or MADL. It makes sense that we would be concerned about these limits, since a substance could have a really low level of a contaminant, but that can still add up if you eat enough of it. Two grams of sugar in a low sugar yogurt is hardly anything, but if you eat 20 yogurts, you’re now looking at 40 g of sugar.

For these daily limits, CR says, “We estimated a U.S. infant’s daily intake (12 scoops of dry powder for 24 fluid ounces), at 3 months old (with an average weight of 6.1 kg, or 13.4 pounds), of the tested aluminum, acrylamide, inorganic arsenic, bisphenol A, cadmium, lead, or PFOS for each model and, where appropriate and applicable, compared the intake estimates to the exposure limits in the table below.”

This estimate immediately caught my attention, since I imagine that different scoops for different formulas probably measure different masses of powder. I also know that our formula (Kendamil Organic, cow’s milk based) requires a 1 fl oz to 1 scoop of powder ratio, so 12 scoops would only make half of a 3 month old’s average daily intake. I had read on Reddit that some formulas make 2 fl oz with one scoop, so it’s brand/model dependent (always consult the back of your formula label!!!). I reached out to the author of the CR article, Lauren Kirchner, to communicate these concerns. She reassured me that they did take into account different scoop sizes and different numbers of scoops by relying on formula mass, but they just said 12 scoops to simplify things. I’m glad this is the case, but I do think the Methodology part of the report should be more specific about the amount of formula used. If they wanted to keep it extremely simple and confusion-free, they could have said that they measured out the mass of formula required by each formula brand/model to make 24 fl oz.

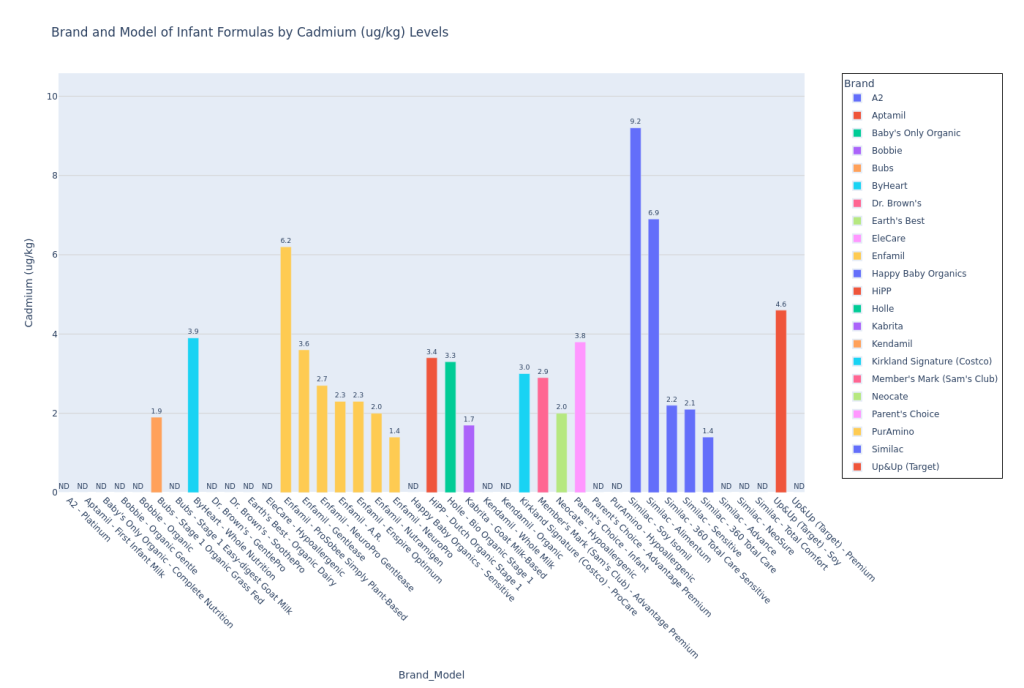

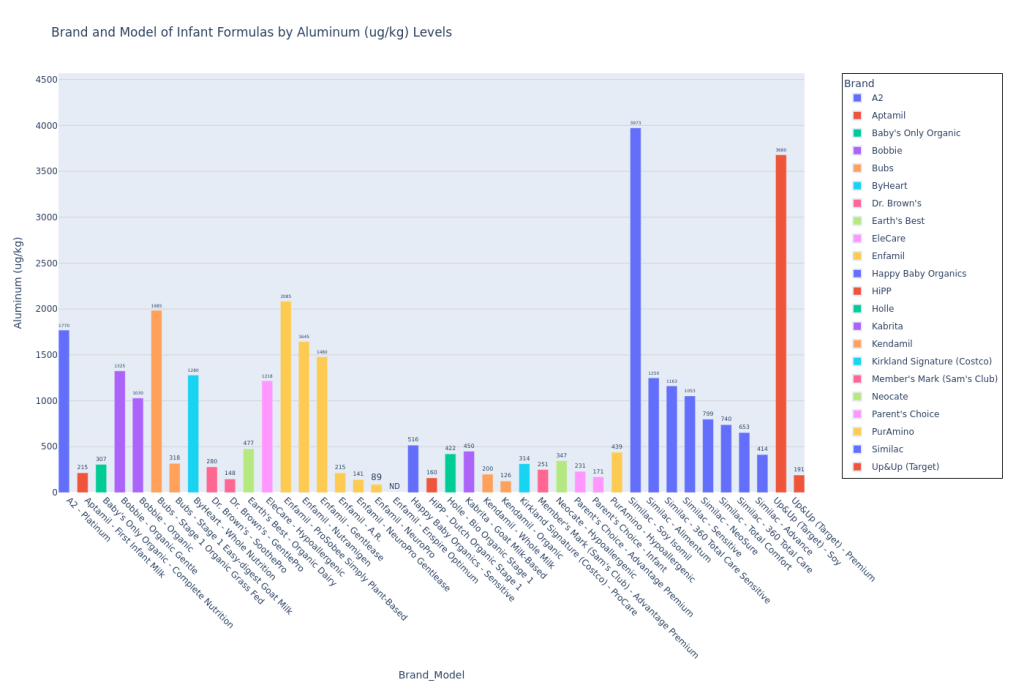

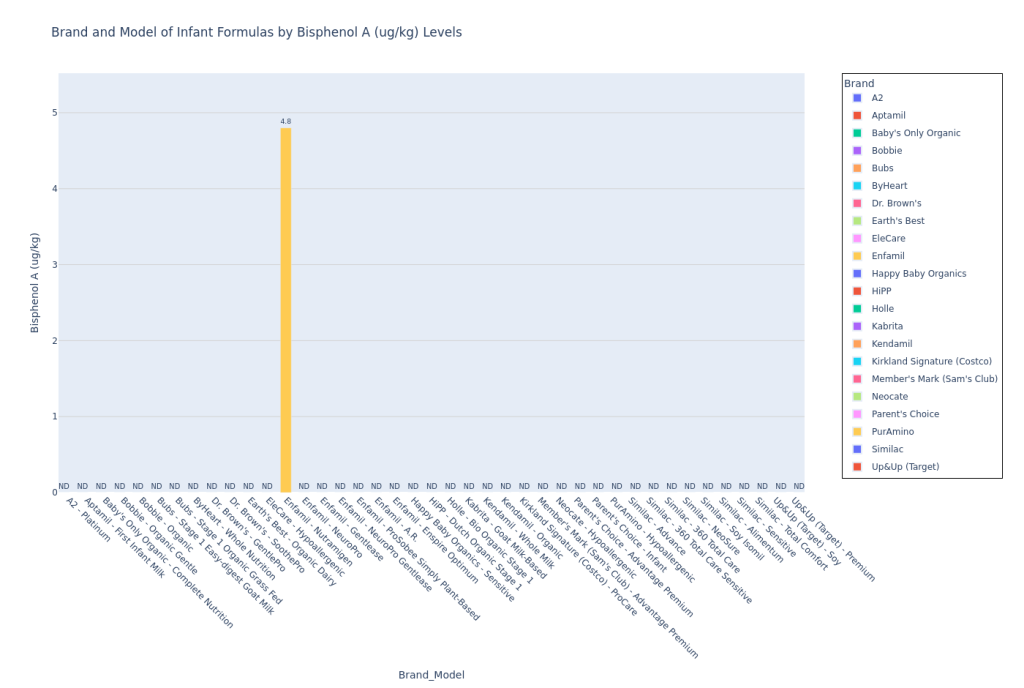

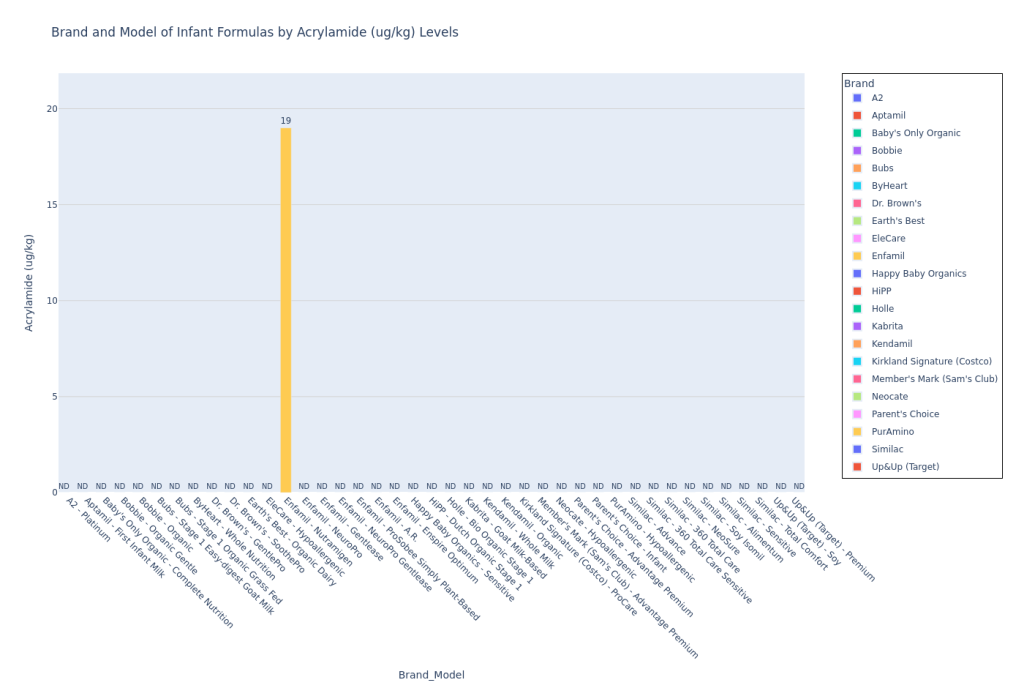

Grappling Graphically

I used Claude (LLM) to convert the Consumer Reports test results pdf to a csv, and then I used Python (and a lot of LLM help!) to plot the data. Here’s my code on Github to plot the data. I pulled the Consumer Reports data on April 9, 2025, so please note that if any corrections were added by Consumer Reports to the data after that, the data could be incorrect. Mercury (Hg), Bisphenol F (BPF), and Bisphenol S (BPS) were not detected in any formula samples. If a formula model was not tested for a contaminant (marked “NT” on the pdf data table), then I did not include this model on the bar chart for that particular contaminant.

These are not the most insane bar graphs you’ve ever seen, but they get the job done for you to at least locate your formula and see how they stack against the others, at least for the CR contaminants report. I am leaving out the potassium bar plot since the CR article said (also quoted earlier in Methodology), “This was a check on the formula’s nutrition content, not its potential contamination. In 2024 the FDA put out warnings for certain formulas because they had excessive levels of potassium, which can be dangerous. The good news here is that none of the potassium levels measured in CR’s tests were over the maximum limit set by the FDA. Some of the formulas tested below the lower limit, but they weren’t so low as to be of concern.” I personally felt that if I included this plot, parents who are skimming this article may be confused and treat it like lead or arsenic (higher amount in one formula would be worse than a lower amount in the other). Since potassium levels are clearly more nuanced than that and since Consumer Reports wasn’t concerned by any of the levels in the tested formulas, I just decided to leave it out.

Lead in Kendamil Organic

Ok, I apologize to the parents reading this article who are using a different formula. I just wanted to dive into Kendamil Organic lead content because it directly affects my son and therefore captured my energy and attention.

I will include more information in Part 2 of this article. Here’s the breakdown I currently have.

There are multiple EU regulations on infant formula, so I asked ChatGPT what the most recent document is. The LLM told me that the most recent is Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 from May 25, 2023. This regulatory document sets the limit for formula powder at 0.02 mg/kg, which translates to 20 ug/kg, or 20 parts-per-billion (ppb). Some follow-up questions I need to investigate and publish in Part 2 of this article are: 1) Is Kendamil regulated by the EU? (I have seen parents and Facebook peeps claim this, but I haven’t fact-checked this yet. Since Kendamil is UK-based, I’m not sure if Brexit would have affected its relationship to EU regulation or not), and 2) How did the EU derive this limit?

Consumer Reports chose to use a conservative California lead health limit (Maximum Allowable Dose Level, or MADL), which you can see on California’s health site here. Under “Safe Harbor Levels,” the Reproductive Toxicity MADL (used by CR) is 0.5 ug/day. However, “Safe Harbor Levels” also includes a second limit with a “Cancer” label (instead of “Reproductive Toxicity”), called the “No Significant Risk Level (NSRL) – Oral,” which is set to 15 µg/day. In Part 2 of this article, I will explore the differences between these limits. I have seen some preliminary information with an LLM and I have emailed the California contact on their health website.

I did back-of-the-napkin math for my son’s lead exposure. If 1 scoop of Kendamil Organic is 4.3 g, if we assume that the amount of lead detected by CR labs in Kendamil Organic (3.1 ug/kg) is constant across all lots (I know, probably not a great assumption, but it’s what we’ve got), and if my son currently consumes about 31 scoops of Kendamil Organic per day, he would consume about 0.41 ug of lead per day. If you consider that there could be lead in the water or that he will soon be eating more formula (we are still adding a small amount of breastmilk to his formula but will be discontinuing soon), we are very close to meeting or even exceeding the California Reproductive Toxicity MADL. I am currently considering switching him to the Classic Whole Milk Kendamil for this reason, although I will deliberate further and detail my thought process in Part 2 of this article.

What Else Makes a Good Formula?

Ok…this is a really big topic. While I was skimming an EU regulatory document, I saw lots of interesting information about bringing formula content closer to breastmilk with amino acids and proteins and other unique components. When I have time, I will do a deeper dive into this and compare to U.S. formulations and regulations.

For this article though, I want to highlight that contaminants like those investigated by the CR article are just one piece of the puzzle for determining a good formula.

One New York Times Wirecutter article breaks down some of the basics. First off, you want your sole carbohydrate to be lactose, the natural sugar in milk. It’s probably not a surprise that you should be more skeptical of formulas with corn syrup as the primary carb. You may also need to get a formula with partially broken down proteins if your pediatrician recommends this course to ameliorate digestive issues. The article also mentions whole cow’s milk base vs. skim milk base and cow’s milk vs. goat’s milk. I would like to research these topics further, along with understanding DHA and HMO’s and prebiotics. I don’t currently have the time, but I will continue to research and release more articles after this one. The main point I want to make is that there is more to consider in a good formula than contaminant levels.

Holding the FDA Accountable

The CR article relates a history of formula in the U.S. and it isn’t pretty. Originally, there were no regulations. Two mothers of babies who became very ill after a formula company removed an ingredient lobbied the U.S. government and began a publicity campaign. Because of their efforts, the Infant Formula Act was passed into law in 1980. Now, the FDA regulates nutritional content and bacterial contamination, but they have very little oversight of contaminants like lead or arsenic. CR mentions that the FDA has done some light testing and they do have some reactive measures (rather than preventive) in place, but these are limited and most of the burden lay on the formula companies themselves.

One day after CR shared the formula contaminant results with the FDA, the FDA launched Operation Stork Speed to address contamination concerns and lack of regulation. CR seemed a little skeptical, however, based on recent cuts to the FDA and lack of resources.

I am also skeptical. A New York Times article from March 19 of this year explains the role that regulators and inspectors play in the food supply and how funding cuts during both the Biden and the DOGE era can negatively affect public safety. The article does focus more on the risks of bacterial contamination in formula and notes that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., did initiate Operation Stork Speed, a fact I did not know beforehand. In the HHS release about Operation Stork Speed, HHS Secretary RFK Jr. says, “The FDA will use all resources and authorities at its disposal to make sure infant formula products are safe and wholesome for the families and children who rely on them. Helping each family and child get off to the right start from birth is critical to our pursuit to Make America Healthy Again.”

While this sounds great, we need to hold the FDA accountable and make sure they follow up. The NYT article mentioned above details how important preventing bacterial contamination can be and how federal and state regulators need federal funding to keep our kids safe. The author also mentions a recent incident of lead contamination found in applesauce pouches for kids. In our current climate of DOGE spending cuts, will our bureaucracy continue to have the resources to fight contaminants, both bacterial and chemical?

Additionally, Kyle Diamantas is “the FDA’s top food executive” (FDA site). The New York Times reported that Diamantas “was in recent months a corporate lawyer defending a top formula maker from claims that its product gave rise to debilitating harm to premature babies.” This “top formula maker” was Abbott, the same company whose plant was shut down in 2022 for bacterial contamination. They make EleCare and Similac branded formulas. So yeah, will the FDA really have our babies’ best interests in mind?

If you’re feeling skeptical too, Consumer Reports has a petition you can sign with a message to HHS Secretary RFK, Jr. You can sign here.

Please comment with your feedback! I love to hear from you!

Corrections

4/16/2025: I updated the article to reflect that the FDA announced Operation Stork Speed a day after CR shared their findings with the FDA. Previously I had said that the FDA made this announcement because of the CR findings. While this causation (CR report -> FDA announcement) may be true, I do not know for sure if it was a direct causation or maybe a coincidence (unlikely, I know). CR strongly suggested a link, but I want to be careful. So, I changed my wording to be more fact-based and not so firm on a causal link.